Race and separation in the UMC

Race and segregation has been in the UMC since its inception. For almost its first 100 years, the church was segregated either at the local church, where the groups worshiped at different times, or in different spaces. As the Black membership grew, segregated churches, managed by white pastors, were developed in segregated districts. African Americans were allowed to be local preachers, which tied them to a particular church. At this time, African Americans were denied, by in large, ordination, which would have allowed them to led churches.

In 1864, almost 100 years after the plea to John Wesley to send lay preachers, African American annual conferences were developed, which allowed ordination for Blacks as well as a real degree of leadership. The first was the Delaware Conference in 1864, which covered the area of the Delmarva Peninsula, parts of Maryland, New Jersey, and New York.

In the South after the completion of the Civil War, a series of conferences were started. Most of these were heavily African American. Between 1876 and 1880 these were segregated.

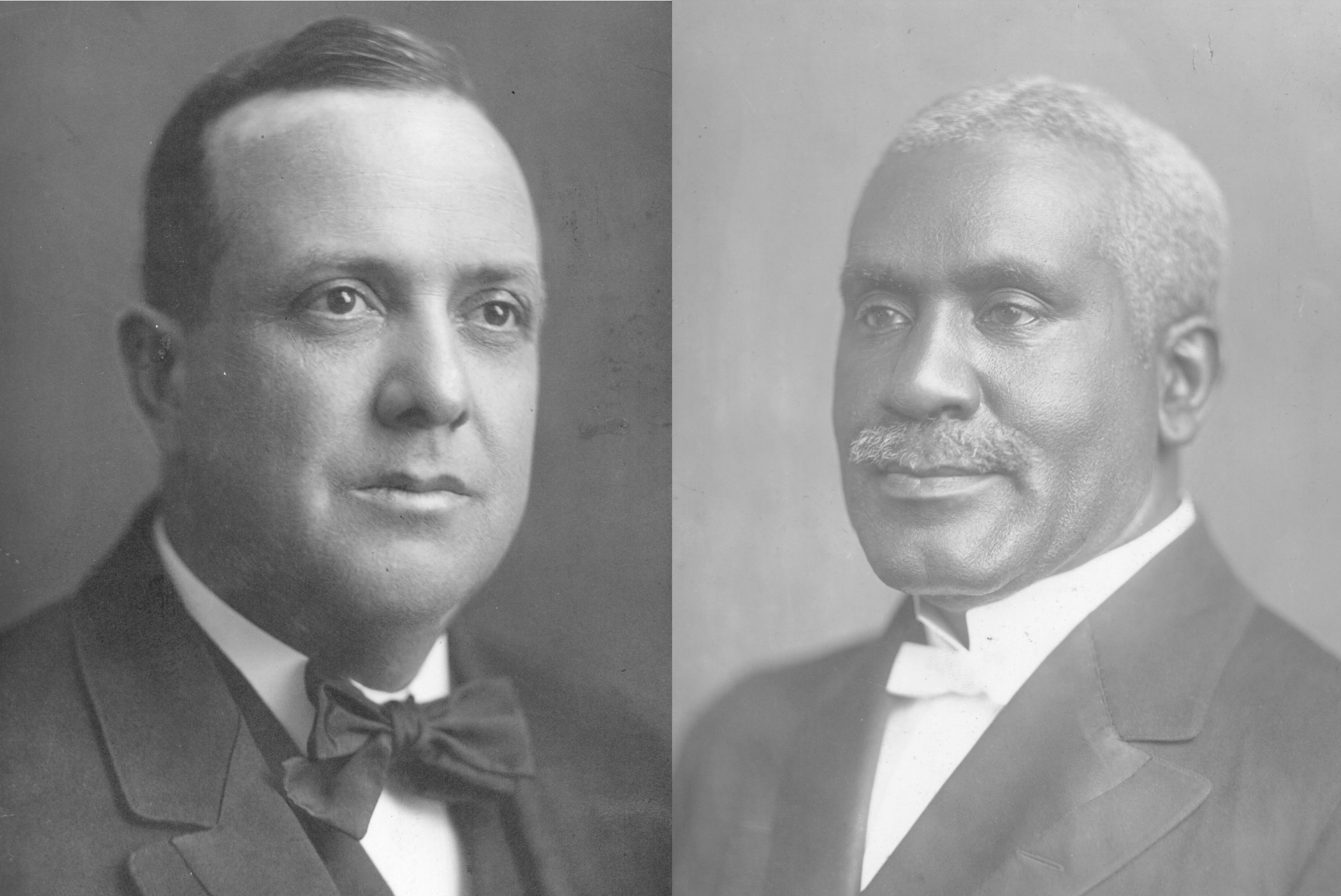

In the early 20th century, two African American bishops were elected in segregated voting at the General Conference — R.E. Jones and Matthew Clair. They would eventually be assigned to the southern African American conferences while whites still managed the segregated conferences in the north. Jones had been the editor of the Southwestern Christian Advocate, the church newspaper for the African American Methodist.

In 1939, the Creation of the Central Jurisdiction was meant to separate and divide. It formalized the segregation of the church under stricter and more odious methods. The Plan was repudiated by the African American churches.

From its beginning, there was resistance to the Jurisdiction. In 1956, Amendment IX allowed a church or annual conference to transfer to a new jurisdiction and conference. However, it offered no timetable for the completion.

In 1960, the “Committee of Five” of the Central Jurisdiction recommended that as many of its churches and conferences transfer by 1968 as possible. The Committee also recommended a set of requirements before a transfer or merger that would help to keep the minority group from being segregated again within the new jurisdiction or conference.

Union but perhaps not unity

The Central Jurisdiction was gone by 1968, but there were still segregated conferences in the new denomination. For many, the desire had been to do away with segregated conferences, but the Plan of Union stopped using the old language while allowing for the old reality. However, the push continued and, by 1972, merger of the remaining segregated conferences was completed under the watchful eye of the Commission on Religion and Race. The Commission worked with most of the conferences in integrating along with working on agencies and seminaries to integrate as well. The Central Jurisdiction was gone but most of the challenges which faced the old CJ were still here.

Originally published by the General Commission on Archives and History.