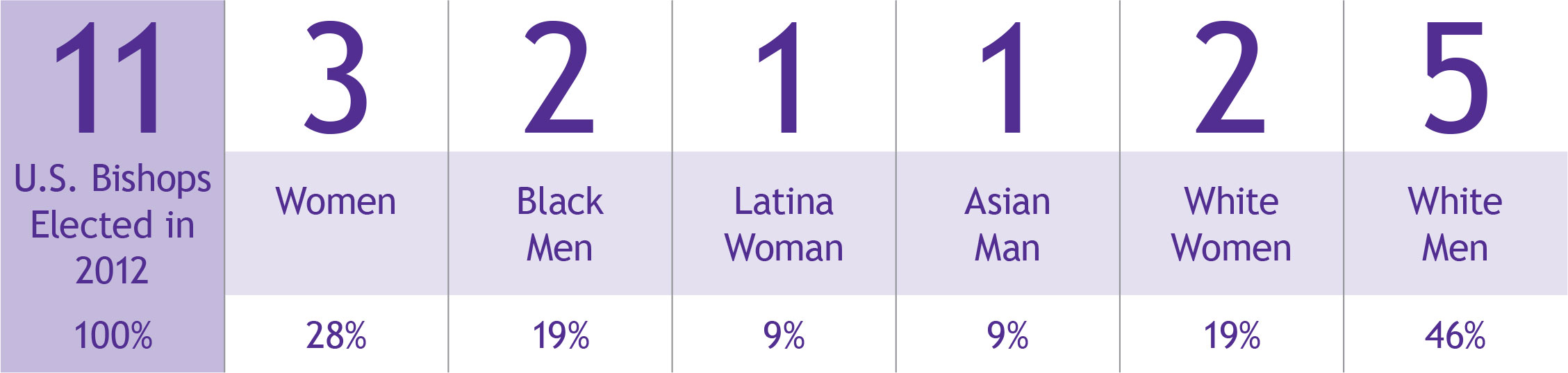

Recently, United Methodists in the United States elected eleven (11) new bishops to fill episcopal seats vacated by retirements. In the United States, the five jurisdictional conferences elect bishops every four years.

For the 2013-2016 quadrennium, there are 140 active and retired U.S. bishops. Out of the 46 active bishops, 11 are women (24%). Of the 11 women bishops, nine are white and two are Latina. No other U.S. racial-ethnic group is represented among active women bishops. This will be the first quadrennium since 1984 that there will be no black U.S. woman among the active United Methodist bishops. The denomination has yet to elect a Native American or Pacific Islander—male or female—to the episcopacy.

During the 2012 gatherings, the Northeastern, Southeastern and South Central jurisdictional conferences elected three women—two white and one Latina.

Of the total number of 11 new U.S. bishops:

Bishops in the United States are elected for life; in the Central Conferences (United Methodist judicatories in other nations) the process varies, from term limits to election for life. There are two women bishops outside of the United States.

In the 2009-2012 quadrennium, there were 49 active bishops, of which 13 were women (27%). Because of mergers of episcopal areas, there are fewer bishops in the 2013-2016 quadrennium.

Five women bishops retired in 2012, and three were elected, so there are two fewer women bishops in the 2013–2016 than in 2009–2012. Northeastern, Southeastern and South Central Jurisdictional retained the same percentage of women bishops, 22%, 18% and 23%. North Central went from 30% to 22% and Western Jurisdiction went from 50% to 40% of women bishops, the two jurisdictions that did not elect bishops and had mergers.

There are 11 retired women bishops, three black women and eight white women. Because there are so many retired bishops (almost twice as many retired bishops than active bishops across the denomination), the role of retired bishops have changed and they have a more limited voice and leadership now than they did in past quadrenniums.

Candidates

According to umc.org, there were 44 candidates for the episcopacy in the United States, even though all clergy are eligible for nominations. Of the 44 candidates, 32 were men (73%) and 12 were women (27%), which is similar to the percentages of women clergy in the United States. Of the 32 men, 19 were white, six were black, two were Latino, four were Asian and one Native American. Of the 12 women, four were white, four were black, three were Latina and one Asian.

Of the 44 candidates, 37 had conference endorsements and 16 had caucus endorsements. (Some candidates were endorsed by more than one caucus.) Of the 37 candidates that were endorsed by the conferences, 29 were men (79%) and eight were women (21%). Of the 29 men, 19 were white, three were Asian, five were black, one was Hispanic and one was Native American. Of the eight women, four were white, two were black, and two were Latina.

Without the caucuses, there would have been fewer women and less racial ethnic people in the pool of candidates. The conferences endorsed all the white candidates and some of the racial ethnic candidates.

With Bishop Linda Lee’s

retirement, there is now

no African-American

U.S. woman serving

among the active United

Methodist bishops.

With Bishop Linda Lee’s

retirement, there is now

no African-American

U.S. woman serving

among the active United

Methodist bishops.

Summary

In terms of race and ethnicity, the 2012 round of U.S. episcopal elections closely match the current percentage of U.S. population, which is approximately 65% white and 35% racial-ethnic.

However, while the 2012 episcopal elections leave a gender ratio that approximates that of the U.S. United Methodist clergy, that ratio falls far below that of United Methodist lay membership—and the U.S. population— which are each about 54% female and 46% male. We challenge U.S. congregations and annual conferences to create pipelines for leadership with a diverse pool of men and women, white and racial-ethnic and interracial people, young people, those who are differently abled, and those with diverse life experiences. While The United Methodist Church seems to have an unending pool of white men to choose from to fill the highest positions, often there is only one or two women and people of color.

If we are to reach and disciple all God’s people, we must demonstrate that we respect their gifts and potential contributions to our denomination.

Magazine sponsors frank talk about race and gender in the workplace

We can learn something from the National Multicultural Women’s conferences and town hall meetings, sponsored by Working Women magazine for more than 10 years.

Participants divide into separate racial-ethnic groups to talk privately about the barriers they face, the obstacles they create themselves and how to move their specific group forward.

Each affinity group also discusses a common topic, such as trust, identity, authenticity, power and interracial relationships. After the discussion, each group reports back in plenary anything they choose to share.

Among the common findings participants report:

- White women are more like to claim that they “don’t see color” and want to join with their sisters of color in the struggle. Further, they are the most uncomfortable of all groups with the idea of talking in single-race groups.

- Women of color often perceive white women as having pushed their way up the ladder of success, without regard to—or even at the expense of—women of color.

- African-American women, the second largest racial group (after white women) in all the meetings, admit they trusted white women only half as much as they trust members of other racial groups.

- African-American women are more likely to self-identify according to race first, and say racial dynamics are more of a factor than gender in the workplace. For example, a Chinese American woman said she thought of herself first as a “pushy New Yorker.” An African-American woman said she felt that her own skin color “walks into the room with her” and leads to immediate stereotyping and bias. The exchange led to a raw and honest discussion about what particular groups of women experience in corporate settings.

- Latinas cited intergenerational issues, language barriers and bias against their style of dress as hindering their advancement in the workplace.

- Native American women are the smallest and least visible group of women at these gatherings (the same is generally true in United Methodist Church settings), and members of that group talked of being completely isolated in their workplaces. Other women admitted that they usually can find another woman from their group.

- Women who consider themselves multicultural or of mixed racial heritage have begun to create their own group at the Working Women gatherings, and say they find it liberating to break free from single-race labels because, in fact, they must navigate several worlds.

What the corporate workplace—and church—can learn from intentional conversations and actions around race and gender:

- Agencies that welcome and value cultural diversity among employees (and volunteers) help connect to an array of people and communities and develop resources (and ministries) to attract and serve more people.

- Diversity doesn’t just happen. Those companies most effective in serving diverse groups create pipelines to recruit and nurture racial-ethnic people for future leadership roles.

- Go to where young people of all colors are to find new members, volunteers and ministry opportunities. Places include seminaries, college campuses and social media.

- Offer ongoing leadership training for high-performing staff that includes “unwritten rules” of success; and connect up-and-coming staff with senior leaders.

- Attend conferences or host events that bring talent to the attention of managers. Affinity groups play an important role in providing information for women of color about job openings.

- Provide summer internships for high-school senior level multicultural girls. Give them early exposure to the corporate culture and help influence their future career choices.

- In many ways, the corporate world has outpaced United Methodist recruiting, training and retaining women and people of color as key decision-makers, ministry leaders and innovators. Secular companies have learned that reaching diverse and new audiences can increase profits.

If the church is committed to making Christian disciples and transforming the world, then we as a denomination, as local churches and as parishioners, must also increase our efforts in reaching women and people of all colors. The U.S. membership in The United Methodist Church is about 95% white; if your ministry is more diverse, what success stories can you share? And if you are not embracing diversity, what do you need from the denomination to help you widen your scope?