For over a century, United Methodists and their predecessors have been advocating for fair labor practices. And while today's society looks much different than that of 18th-century England where John Wesley and the early Methodists ministered to coal miners and other marginalized workers and their families, many current advocates say the same principles apply more than 200 years later.

"The 1908 Social Creed really spoke to the moment of realizing the impact of the industrial revolution on society – the ways in which people's lives and communities were impacted by the economy that was changing around them," said John S. Hill, director of environmental and economic justice at the General Board of Church and Society. "And I think similarly our current Social Creed is a reflection of how these systems are impacting us and how we need to engage not just from a personal individual level, but through challenging those systems."

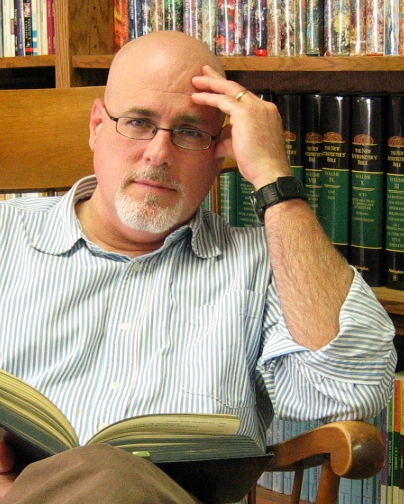

The Rev. Darren Cushman Wood, author of Blue Collar Jesus and pastor at North United Methodist Church in Indianapolis, said promoting economic justice has "always been a stream of our social witness.

"It comes out of our notion of holiness. Holiness has to be a transformation of the whole person – body and mind, our social and economic relations as well."

As outlined in the 1908 Social Creed and still present in the denomination's Social Principles today, a belief in God-given human dignity undergirds United Methodists' historic emphasis on worker justice.

Dignity found in all work

"We are created as partners with God in taking care of the earth," said the Rev. Mark Galang, pastor at Beacon United Methodist Church in Seattle. "Being partners with God in caring for the world gives dignity to the work that we do, and the work we do then becomes an expression of our faithfulness to the call of God to be stewards of the world. Thus, because we are partners with God in our work, every working person must be treated with due respect and dignity."

The Rev. C.J. Hawking, executive director of Arise Chicago and pastor of social justice at Euclid Avenue United Methodist Church, said her work with others has proven that, regardless of career path, dignity abides within the worker. Arise Chicago is credited with securing passage of anti-wage theft ordinances in Chicago and Cook County

"I believe we were all designed to work, to contribute to the common good," she said. "We each have creativity and drive within us that wants to make the world a better place. Whether you're a janitor keeping a workplace healthy and clean or you're the accountant making sure the books are balanced or you're a flight attendant – every single job has dignity. Virtually everyone I have met takes pride in their work and sees it as contributing to the common good."

Living wage struggle continues

For many United Methodists, the fight for workplace justice involves fair wages, earned sick time, paid maternity leave and safe conditions.

"We have been calling for a living wage in every industry since 1908," Hill said. "I reflect on both how inspiring that is and how frustrating that is, that we are still so far away from realizing that in our society. But it's really sort of a testament to me of what has come before, the work that we're building on and then the work that's yet to be done."

Hawking sees progress but also a need for more transformation.

"This is an exciting time to engage in workers' rights," she said and added, "We need to develop workplaces that reflect our values."

"We all say that we support family, but we need wages to follow that," she said. "If someone is paid minimum wage, they often have to take a second job to make ends meet. That takes a person away from their family and their community because they're working all the time. Fair wages really impact our communities in so many ways."

Galang thinks it's important to integrate faith and work by seeing good in others and seeking their good, including advocating for their rights.

"As people of faith we believe in justice and fairness," he said. "We have to be concerned not just about ourselves but for the good of all. Thus, we speak up and fight until everyone has enough because, until then, no one is really free."

Healthy relationships give witness

Cushman Wood also emphasized the value of healthy work relationships.

"Being supportive of your coworkers is a profound witness for the gospel," he said. "Especially if there are coworkers struggling at work, for you to be collaborative instead of competitive, that makes all the difference in the world."

According to Galang, who works with a group called Interfaith Economic Justice Coalition, dignity in the workplace has to come from both the employer and the employee.

"The work that we do and how we do it is an expression of our faithfulness to God's call to us," he said. "Finding worth in the work we do builds confidence and self-esteem that leads to worker dignity. I believe before we expect others to treat us with dignity in our work, we first have to find joy and worth in our own work. I think this is the employee's foremost responsibility to their employer – to promise to find dignity in their work and do the best they can in performing it."

Hill said everyone could strive for a more dignified global system of work by being more aware and intentional in their purchases.

"Understanding all the hands that toil and the workers that labor to support our daily lives is a good start," he said. "From the farm workers who harvest our fruit and vegetables, to the garment workers who sew our clothes and the miners who risk their health and lives so that we might have energy and minerals to power our modern economy – our daily lives are linked to the work of others. As we trace those connections, we must start asking how often we are valuing convenience and price over faithfulness and right relationships with others."

Emily Snell is a freelance writer based in Nashville, Tennessee, who writes frequently for Interpreter and other publications. She recently joined the staff of The Upper Room at Discipleship Ministries.

Originally published in Interpreter Magazine, September-October, 2017.