Stand Your Ground Study Questions

Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God

by Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas

Study Questions written by:

Kristin Henning, Agnes N. Williams Research Professor of Law; Assoc. Dean for Clinics and Centers; Director, Juvenile Justice Clinic; Georgetown Law

Week one: Prologue and Introduction, vii – xv (9 pages)

1. Who is Kelly Brown Douglas? (May require outside research.)

2. What motivated Kelly Brown Douglas to write Stand Your Ground? p. ix. What questions does Douglas seek to answer in writing this book? What else does she hope to accomplish? pp. ix, xi, xiii

3. Where were you when you first heard about the killing of Trayvon Martin (February 26, 2012)? What impact did that killing have on you? What outraged you? What was surprised you, if anything, about this killing and the nation’s response?

4. If you were alive at the lynching of Emmett Till (August, 1955), do you remember where you were at the time? What impact did that lynching have on you? What social, cultural, and political similarities do you see between the killing of Trayvon and the lynching of Emmett Till?

5. How did black churches initially respond to Trayvon Martin’s killing? p. xii How have black churches continued to respond to the killing of black bodies? What more should we be doing? (GCORR note: how did the United Methodist Church respond, how did your church respond?)

6. What are the unique challenges of raising a black son in America? p. xi

7. As you contemplate the full title of Kelly Brown Douglas’ book Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God, what questions do you have about the “justice of God”? How do we understand the justice of God in the face of killings of young black boys like Trayvon Martin?

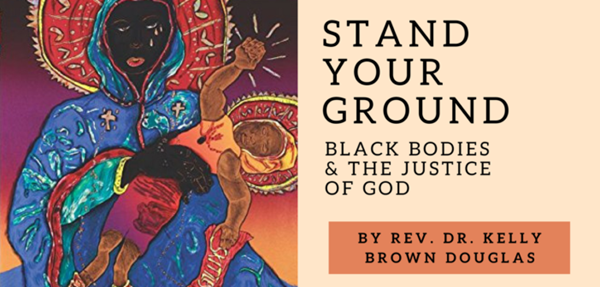

8. Study the artistic cover of Stand Your Ground. What are the key features of the cover? What meaning do these key features signify for you?

9. Before reading Douglas’ book, what did you know about “stand your ground” laws? What are the social and cultural implications of stand your ground laws as you currently understand them?

10. After looking at the table of contents, what do you hope to get out of Douglas’ book? What are you most excited about or most interested in?

Week two: ch. 1, America’s Exceptionalism, pp 3-47 (44 pages)

1. What is the Anglo-Saxon myth and how did it evolve? pp. 6-7 How did this myth move from England to America? pp. 7-11 What role did religious reformers play in transporting and legitimizing the Anglo-Saxon myth to America? pp. 8-11 The 98 C.E. text Germania, written by Roman historian Tacitus, has been called “one of the most dangerous books ever written.” p. 4 Why? What are the key premises of Germania? pp. 4-6

2. Kelly Brown Douglas describes democracy and freedom as two key components of the Anglo-Saxon myth. p. 10 How do these themes play out within the myth?

3. How did influential national leaders like Thomas Jefferson perpetuate Anglo-Saxon chauvinism? pp. 11-12

4. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what are the two religious “canopies” that legitimized the Anglo-Saxon myth? pp. 9, 12-14

5. What does the term “America’s exceptionalism” mean? p.15

6. How did America’s exceptionalism transform from its initial institutional focus (i.e., democracy, liberty, institutional rights) to its subsequent racial focus? pp. 15-23

7. What role did Benjamin Franklin play in that shift? pp. 16-17

8. What role did Ralph Waldo Emerson play in that shift? pp. 18-21, 23-25

9. What role did Romanticism and philological studies (the study of human origins) play in that shift? pp. 18-21

10. How did America’s social and political leaders connect race and language in their quest for human origins and in their understanding and articulation of the narrative of America’s exceptionalism? pp. 21-22

11. How was science used to manipulate or manufacture Anglo-Saxon superiority? p. 25

12. How was religion used to legitimate America’s exceptionalism? p. 25 Why was it so important to validate exceptionalism through religion?

13. Kelly Brown Douglas writes that “Anglo-Saxons are not native to American soil. … And those native to American soil are decidedly not Anglo-Saxon.” p. 27 How does this Anglo-Saxon immigrant reality create a “paradox” for America’s exceptionalism and the Anglo-Saxon myth? pp. 27-28

14. What was President Roosevelt’s strategy (and the strategy of other presidents) for protecting the Anglo-Saxon identity of America and regulating the influx of immigrants? pp. 29-33 What immigration laws emerged in an effort to protect America’s exceptionalism? pp. 31-33 How do those laws compare to contemporary immigration legislation?

15. How did the Protestant Evangelical community respond to the influx of new immigrants and seek to protect the Anglo-Saxon myth? pp. 33-34

16. How did the “new stock” of immigrants use their “whiteness” to negotiate their security, power and American identity? pp. 34-40 How and why did this new stock of immigrants construct their new identity in opposition to blackness? pp. 36-40

17. What does Kelly Brown Douglas mean when she writes about “whiteness as cherished property”? pp. 40-44 What does W.E.B. DuBois mean when he talks about the “wages of whiteness”? p. 41 How does blackness get constructed as sin and whiteness as sacred property? pp. 42-43

18. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what is the “stand your ground culture” and how does it protect whiteness? p. 44

19. What advice and strategies does Kelly Brown Douglas offer for raising black sons? p. 46 Do these strategies resonate with you? What strategies would you add?

Week three: ch. 2, the black body: a guilty body, pp 48-89 (41 pages)

1. Kelly Brown Douglas talks about the “theo-ideological” framework that has evolved to subordinate black bodies. pp. 50-51 What does Douglas mean by this? How does the theo-ideological framework of black threat protect the grand narrative of America’s exceptionalism and justify brutal assault on black bodies? p. 50 How does this play out today?

2. What is St. Thomas of Aquinas’ theory of natural law and how did that theory work to exclude blacks from citizenship and humanity? pp. 51-52, 56 How was the very fact of black enslavement used to demonstrate that blacks were “meant to be” subordinated and enslaved? pp. 56-57

3. What does it mean to be a “commodified body”? What implications does commodification (or the designation of the black body as “chattel”) have on the natural and legal “rights” of black people? pp. 52-55

4. How did whites use the theory of natural law to portray black freedom as sin and wickedness? pp. 58-59 Note: What does ontological mean? p. 50 What is an “ontacracy”? p. 59 What is an ontological danger? p. 70 What are the nomos and comos? p. 70

5. How does the Anglo-Saxonist natural law cast God as both Anglo-Saxon and a white supremacist? p. 60 How does this conceptualization of natural law contradict central doctrines of Christian faith? pp. 60, 64 How does this conceptualization contradict black faith? p. 60

6. How does the theory of natural law “morally compel” whites to protect their freedom and prevent intrusion into white spaces? p. 60

7. How did whites use science or “religio-science” to support different creation narratives for whites and blacks? pp. 61-64 Who was Louis Agassiz and what is polygenetic religious science? p. 61-64

8. What is the narrative of the “hypersexualized black body”? pp. 64-68 What purpose did this narrative originally serve for whites? pp. 65-70 How did whites come to see the hypersexualized body as a hyperviolent, threatening body? p. 67 What purpose does this narrative continue to serve in American society?

9. How is “freedom” for blacks uniquely dangerous according to the theory of natural law? pp. 68-69 How does black freedom endanger the narrative of white supremacy and Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism? pp. 68-69 How did the “free black male” become the greatest peril of the post-emancipation era? pp. 70-74

10 According to philosopher Michel Foucault, how does power (especially inequitable power) operate to sustain unjust social structures, even in the absence of brutal force? pp. 74-75 How does Foucault’s analysis help us understand the subtle way in which the images of the “black body as chattel” and “the black body as a violent body” were implanted into the collective psyche of the American society to legitimize the social, political, and institutional constructs of power itself?

11. How has the notion of the “black body as chattel” survived after the era of chattel slavery? How has the concept been transformed in the 21st Century? p. 76

12. How was the notion of the “black body as criminal body” constructed and embedded in American society during Reconstruction (1865-77)? pp. 77-81

13. How has the mass media replaced religion and science to become the new promoter of the black body as a criminal body and a guilty body? pp. 81-84, 86 What is the new “evidence” that the black body is criminal?

14. How have black women been portrayed in the media? pp. 84-85

15. How does Kelly Brown Douglas answer the question “Why are black murder victims put on trial”? p. 87

16. Kelly Brown Douglas prays that black children like Jordan Davis will be seen as the children of God whom they are. p. 89 What prayers do you have for black children?

Week four: ch. 3, manifest destiny war & excursus: From tacitus to trayvon, pp 90-134 (44 pages)

1. What is Manifest Destiny and how did it originate? pp. 96-97, 93-94 What are the prevailing themes of America’s notion of manifest destiny? pp. 95 – 98 How are land and race connected in America’s narrative of manifest destiny? pp. 96-100

2. Why was America’s Manifest Destiny project so urgent both at home and abroad? pp. 97-100

3. What did John Quincy Adams mean when he suggested that the success of Manifest Destiny required the United States to be a unified nation? pp. 99 – 101 What implications did that have for Native Americans and African Americans? pp. 100- 102

4. How did race dictate the right to life and land? pp. 101-02 What does Manifest Destiny say about who is destined to live and who is eligible for extinction (i.e. extermination)? pp. 102, 108 (Foucalt)

5. How were religio-scientific theories used to support America’s claims of Manifest Destiny and to justify white domination and extinction of non-white races? pp. 102- 04 How do we understand the term “melting pot” today? How was the concept of “melting away” understood before the early 20thCentury? p. 103

6. Read Exodus 3:7-22 and Deuteronomy 31:3-8. How have Black Americans traditionally read and understood the Exodus narrative? How did white American settlers use the Exodus story as biblical precedent (and theological justification) for America’s Manifest Destiny? pp. 105- 106 How do we as black Christians grapple with this treatment of the Exodus as a narrative of domination instead of liberation? p. 106 How does this reading of Exodus challenge our faith and our understanding of liberation theology? [NOTE: We will discuss this in greater detail next week]

7. How does the narrative of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism exonerate whites from immoral, dehumanizing and even deadly treatment of non-white bodies? p. 107 How does Manifest Destiny become a declaration of war against nonwhite bodies who refuse to assimilate? pp. 108-09

8. What was the Monroe Doctrine? pp. 109-10 And how did it embody the arrogance of America?

9. How is the war of Manifest Destiny a religious war? pp. 110-111 What is the “just war theory”? What are the six purported requirements for a just war? p. 111

10. What is the stand-your-ground culture that Kelly Brown Douglas describes in this text? p. 112 How does the contemporary stand-your-ground culture carry out the war of Manifest Destiny today? pp. 112-14

11. How did the Anglo-Saxon Manifest Destiny mission of land, race, and life intrude on Native American bodies? pp. 113-14

12. What is the Stand Your Ground law? p. 114 What events led to the first Stand Your Ground law? p. 114 What role did the NRA and organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) play in the passage of Stand Your Ground laws across the country? p. 115 What implications do these laws and support from these organizations have on black bodies? pp. 114-15

13. Kelly Brown Douglas contends that the stand-your-ground culture has been most aggressive after every historical period in which new “rights” were extended to blacks (e.g., after emancipation, after the civil rights era, and after the election of the first black president). p. 117 What evidence supports Douglas’ position throughout history? pp. 116-25

14. How does the current stand-your-ground culture that contributed to Treyvon Martin’s death mirror the culture of lynching that led to Emmett Till’s death in 1955? pp. 121 – 22 (How do these deaths challenge our understanding of God and justice?? We will explore this question in greater depth in chapter 5.)

15. How did restrictive housing laws protect cherished white culture? p. 123 How did the U.S. Supreme Court assist in protecting white space in the housing debate? p. 123 How has the Supreme Court continued to protect white space in and beyond the housing context?

16. What strategies did white politicians adopt after the 1960s civil rights struggle to return black bodies back to chattel slavery? pp. 125 -26 How were land, space, race, and life linked in the War on Drugs and the criminalization of blackness? pp. 127-29

17. How did blacks seem to threaten the core of America’s exceptionalist identity in the civil rights era? p. 127

18. Kelly Brown Douglas believes the current stand-your-ground shootings are whites’ backlash to the first black president? pp. 130-31 Do you agree?

Week five: ch. 4, A father’s faith: the freedom of god, pp 137-170 (33 pages)

1. Two faith narratives emerge from the Exodus story. What are they and how do they differ? p. 137 Black Christians have always had to grapple with the contradictions and paradox of black faith. pp. 138-39 How did black faith persist in the face of slavery? pp. 138-39

2. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what is faith? p. 139 How do blacks negotiate the space between black life and black hope? p. 140

3. Throughout this chapter, Kelly Brown Douglas collects faith testimonies (e.g., spirituals) of black enslaved bodies? pp. 140-154 Which, if any, of these speak to you? What role did music play in black protest to America’s exceptionalism? pp. 141-44

4. What does Kelly Brown Douglas mean by the “freedom of God” and what implications does God’s freedom have for blacks and their faith? pp. 143-44

5. Who is the Great High God that blacks met in Africa before they were captured and enslaved in America? p. 144-47 How is that God different from the God of the slaveholders? pp. 144, 147-49

6. Kelly Brown Douglas highlights an African principle that everything the Great High God creates has sacred value because it is intrinsically connected to God. p. 150 What implications did this principle have for enslaved blacks and their conviction that black bodies were not created to be enslaved? pp. 150-53 Who is Henry Highland Garnett and what did he have to say to enslaved blacks about God and freedom? p. 152

7. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what is the significance of Trayvon Martin “trying to get home” on the night he was killed? pp. 153-54

8. How did black faith provide a counternarrative to the grand narrative of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism? pp. 154-56

9. How did enslaved black Americans identify with the Exodus story? p. 157-59 According to African American readings of the Exodus narrative, what moved God to act? pp. 157-58 How does Kelly Brown Douglas help us understand the concept of chosenness in the Exodus story? pp. 159-60

10. How do we reconcile the aspects of the Exodus story that allow for the occupation of an inhabitatedland of the Canaanites and others? pp. 160-61 How do we understand the perspective of the Canaanites who were displaced? What additional problems and challenges does theologian Delores Williams highlight in the Exodus story? p. 161 How does Kelly Brown Douglas attempt to reconcile these challenges? p. 162-63 Douglas seems to be trying to answer the unanswerable. Is her answer satisfying to you?

11. What is the paradox of black faith? pp. 164-65 Like James Cone and Howard Thurman, Kelly Brown Douglas contends that black faith is not passive. What evidence does she offer to support that assertion? p. 165-66

12. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what does the story of Abraham and Isaac mean in the black faith tradition? p. 164 How would you describe black faith after the killing of Trayvon Martin? p. 168

13. In a sermon, Kelly Brown Douglas asserted that black identity is defined by five things. What are those five aspects of black identity and do you agree with Douglas’ assessment? pp. 168-70

Week six: ch. 5, jesus and Trayvon: the justice of god, pp 171-203 (32 pages)

1. What are the similarities between Jesus’ crucifixion and Trayvon Martin’s killing? pp. 171-72

2. What was the purpose of lynching? p. 173 (How does this resonate with what we learned from James Cone in The Cross and the Lynching Tree?) How is Trayvon perceived and treated as a threat even in death? p. 173

3. How and why did the media and supporters of Trayvon’s killer try to vilify or criminalize Trayvon in his death? How did Trayvon’s parents respond to these efforts? pp. 189-93

4. How did Jesus align himself with the “most scorned and marginalized bodies of his day”? pp. 174-78 (How does this resonate with what we learned from Obery Hendricks in The Politics of Jesus?) How does the crucifixion affirm Jesus’ identification with the “Trayvons” and other victims of the stand-your-ground culture of today? p. 174

5. Do you remember singing Jesus Loves Me as a child? How did you understand God’s love as a child? How does God’s love manifest in life, love, and freedom today, even in the face of deaths like Trayvon’s? pp. 179-80

6. Kelly Brown Douglas argues that the cross represents the height of humanity’s inhumanity. pp. 180-81 What are the “evil crosses” of today?

7. On pages 181-82, Douglas writes of restoration and resurrection of life in the Bible. Is her claim that “Jesus frees people from the clutches of death and restores them to life” satisfying to you? p. 181 How have Trayvon Martin and all the other black males who were gunned down been “restored to life”?

8. How does Kelly Brown Douglas define “violence” and “non-violence”? pp. 183-84 According to Douglas, how does God respond to violence? pp. 183-84 Do you agree with her assessment? Why did Martin Luther King opt for nonviolence? pp. 184-85 Do you believe “violence” is an appropriate and viable response to racial injustice today?

9. What is “redemptive suffering”? p. 186 (We were also introduced to this concept by James Cone in The Cross and the Lynching Tree, chptr 3 pp. 87-92 and chptr 5 pp. 149-150). What is the danger of “redemptive suffering” and efforts to find meaning in suffering? pp. 186-88

10. Kelly Brown Douglas describes stand-your-ground as a culture of sin. pp. 193-96 How does she define sin? p. 194 How does the stand-your-ground culture foster both individual sin and “systemic and structural sin”? p. 195

11. According to Kelly Brown Douglas and liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez, what does salvation mean in a stand-your-ground culture? pp. 195-196

12. What does Douglas mean when she writes of “original sin”? pp. 196-97

13. How does Douglas define God’s justice? How will God’s justice be realized? pp. 197-98

14. What responsibilities do churches (including white churches) have in a stand-your-ground culture? pp. 198-202 According to Kelly Brown Douglas’ research and assessment, why have white churches remained silent? p. 200 Should black churches partner with and/or agitate white churches in the fight for racial equity today, and if so, how?

15. At the beginning of the chapter, Douglas poses a difficult question: “Where was God when Trayvon was slain?” p. 172 How would you answer that question?

Week seven: ch. 6, prophetic testimony: the time of god & epilogue: a mother’s weeping for justice, pp 204-232 (27 pages)

1. What is kairos? Do you agree with Kelly Brown Douglas that we are in a kairos time? pp. 206-07

2. How have prophetic black voices emerged throughout history to hold the nation accountable in the stand-your-ground wars that have violated the freedoms and lives of blacks? pp. 207-08, 212-18 (see e.g, Martin Luther King, Jr., Frederick Douglas, Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells, Phyllis Wheatley, Benjamin Banneker, etc.)

3. What key events occurred in the kairos time of Martin Luther King’s era (i.e., what key events occurred in American history in the months leading up to King’s “I Have a Dream” speech?) pp. 210-11 How did King’s speech expose a nation at war with itself? p. 212

4. Where were you when you heard Martin Luther King, Jr. give his “I Have A Dream” speech? What did that speech mean to you? pp. 208-09

5. How did John F. Kennedy expose and challenge the contradictions of American exceptionalism? pp. 211-12 (i.e., Anglo Saxon exceptionalism v. democratic exceptionalism?)

6. How did Martin Luther King bring together two faith traditions – that of a nation and that of the black community – in his “I Have a Dream” speech? pp. 212-13 How did King describe the black faith tradition? pp. 213-14 How did King describe the nation’s sacred obligations? pp. 214-15 How did King strategically call upon America’s faith in itself in his demand for black freedom and justice? pp. 214-15

7. Kelly Brown Douglas says that King uses the black faith tradition to “signify” upon America’s sense of exceptionalism. pp. 208, 215 What does she mean by this? What examples does she offer? p. 215

8. How does Mary Church Terrell signify against America’s exceptionalism? p. 217

9. According to Kelly Brown Douglas, what is “moral memory” and why is it essential for change and progress? pp. 221-22

10. What is “moral identity”? How does moral identity aid progress? p. 223

11. What is “moral participation”? pp. 223-24 What is praxis as defined by Gustavo Gutierrez? p. 224 How will you personally fulfill the call to moral participation?

12. What is “moral imagination”? How does moral imagination help us envision a way forward? pp. 225-26

Epilogue: A Mother’s Weeping for Justice pp. 228-232 (4 pages)

1. In Matthew’s account of Jesus’ birth, he recalls Jeremiah’s image of Rachel weeping at Ramah (Matthew 2:18). p. 228 Why is Rachel weeping? According to Kelly Brown Douglas, how is Rachel’s weeping a sign of both deep grief and great hope? p. 228 How is Rachel’s weeping juxtaposed with the birth of Jesus? Are you satisfied with Kelly Brown Douglas’ assessment of that juxtaposition?

2. How did the death of Michael Brown replay the narrative of America’s exceptionalism? What strategies did the police and the media use to maintain the stand-your-ground culture after Michael Brown’s death? pp. 229-31

3. What can black mothers do in this stand-your-ground culture? How do they draw upon their faith in God? p. 232